Did anybody ever tell you that grammar is beautiful?

Not the sounds of a language, nor the calligraphy on a page, but the grammar itself?

Then clearly nobody has told you about Arabic grammar.

In this lesson, we’re going to show you the ins and outs of Arabic pronouns—the words for saying “I,” “you,” “this,” “that,” “he,” “she,” and so on.

English only takes it a little bit beyond there. Arabic, by contrast, takes it significantly further. There are subtle distinctions and possibilities in Arabic that go well beyond what English is capable of.

Did you know, for instance, that in Arabic there’s a special pronoun for talking to just two people? It’s called the dual pronoun, and it’s just one of the surprises waiting for you.

The reason we say “beautiful” instead of “scary” is that once you notice how it all comes together, you’ll have no choice but to marvel at its perfection.

Ready? Let’s learn Arabic pronouns, how to use them, and what makes them so unique.

Table of Contents

Table of Contents

- The Lowdown on Arabic Pronouns

- Arabic Subject Pronouns

- Arabic Object Pronouns

- Arabic Possessive Pronouns

- Arabic Prepositional Pronouns

- Arabic Demonstrative Pronouns

- Pronouns in Arabic Dialects

- Conclusion

1. The Lowdown on Arabic Pronouns

As we’ve mentioned, a pronoun in general is a word referring to a specific person, place, thing, or idea after it’s been mentioned. In English, it sounds weird to say “He’s a nice guy” just out of the blue.

But if you instead say “I have a new math teacher. He’s a nice guy,” then that’s the perfect place for a pronoun.

Arabic makes distinctions with its pronouns that English absolutely does not. Colloquial dialects, like Egyptian Arabic, aren’t quite as complicated, but they still count as more complicated than English.

2. Arabic Subject Pronouns

The subject pronouns are the easiest, by far. Check out this Arabic pronouns chart first:

| English | Arabic | Romanization |

|---|---|---|

| I | أَنا | ana |

| you (masculine) | أَنتَ | anta |

| you (feminine) | أَنتِ | anti |

| he | هُوَ | huwa |

| she | هِيَ | hiya |

Those are called the singular pronouns because they refer to one single person. You can see that Arabic is explicit about whether you’re talking to a man or a woman.

Now have a look at these Arabic pronouns with examples:

- أَنا أُستاذ.

ʾanā ʾustāḏ.

- أَنا أُستاذَة.

ʾanā ʾustāḏah.

I am a (female) teacher.

- أَنتِ مُهَندِسَة.

ʾanti muhandisah.

You (feminine) are an engineer.

- أَنتَ مُهَندِس.

ʾanta muhandis.

You (masculine) are an engineer.

- يُمكِنُها تَكَلُّم العَرَبِيَّة و الهِندِيَّة.

yumkinuhā takallum al-ʿarabiyyah wa al-hindiyyah.

She can speak Arabic and Hindi.

- يُمكِنُهُ تَكَلُّم العَرَبِيَّة و الهِندِيَّة.

yumkinuhu takallum al-ʿarabiyyah wa al-hindiyyah.

He can speak German and English.

Now we move up in number:

| English | Arabic | Romanization |

|---|---|---|

| you two | أَنتُما | antuma |

| they two | هُما | humaa |

Whoa, what’s this?

If you can believe it, an ancestor of English used to have this same grammatical feature—the dual pronoun, specifically marking two of something instead of just singular/plural.

As you can see, though, pronouns in Arabic won’t distinguish male from female in the dual.

- هُما يَتَكَلَّمان عَن السِيَاسَة.

humā yatakallamān ʿan al-siyasah.

They (two of them) are talking about politics.

- هُما يُحِبّان الموسيقى و الرَقص.

humā yuḥibbān al-mūsīqā wa al-raqṣ.

They (two of them) like music and dancing.

- أَنتُما عَلَيْكُما الوُصول إلى العَمَل غَداً مُبَكِّراً.

ʾantumā ʿalaykumā al-wuṣūl ʾilā al-ʿamal ġadan mubakkiran.

You (both of you) should arrive to work early tomorrow.

- أَنتُما لَم تَعُدا جُزءاً مِن هَذا المَشروع.

ʾantumā lam taʿudā ǧuzʾan min haḏā al-mašrūʿ.

You (both of you) are no longer a part of this project.

Let’s move up one more step to the last set of subject pronouns in Arabic:

| English | Arabic | Arabic |

|---|---|---|

| we | نَحنُ | naḥnu |

| you (plural masculine) | أنتم | antum |

| you (plural feminine) | أنتن | antun |

| they (plural masculine) | هم | hum |

| they (plural feminine) | هن | hun |

Here, it’s obvious that Arabic wants to be as crystal-clear as possible about the number and gender of the people involved in the conversation. Well, not quite—for talking about mixed groups of men and women, the masculine pronoun is used. You’ll have to guess based on context. That’s what we do in English all the time!

- نَحنُ في مَركَز التَسَوُّق.

naḥnu fī markaz al-tasawwuq.

We are in the mall.

- أَنتُن تَبدُنَّ مُمتازات.

ʾantun tabdunna mumtāzāt.

You (to several women) look excellent.

- هُم يَحتاجونَ إلى المَزيد مِن التَمرين.

hum yaḥtāǧūna ʾilā al-mazīd min al-tamrīn.

They (about several men) need to work out more.

- هُنَّ مُمِلّات.

hunna mumillāt.

They (to several women) are boring.

In the first paragraph, though, we mentioned beauty. This list of Arabic pronouns might not seem beautiful yet, but watch what happens to pronouns when we start talking about verbs.

3. Arabic Object Pronouns

So this is where you may have heard that Arabic verbs are complicated. When a verb has an object, we include it as a pronoun slapped onto the end of the verb. If you know any Indonesian or Malay, the same thing happens with pronouns in those languages.

Each pronoun takes the form of a different suffix. Sadly, these suffixes barely look connected at all to our full subject pronoun paradigm.

Time for another chart to explain:

| English | Arabic | Romanization |

|---|---|---|

| me | -ي | -y |

| you (masculine) | -كَ | -k(a) |

| you (feminine) | -كِ | -k(i) |

| him | -هُ | -h(u) |

| her | -ه | -h(a) |

So when you say “Ahmed sees him,” you’re really sticking the words together like “Ahmed seesim.” The vowels in the parentheses aren’t pronounced if the suffix is part of a word that happens to be at the end of a sentence, or if the word is pronounced independently without a sentence.

These vowels are also dropped in most dialects of Arabic, including Egyptian and Levantine. This is the case with all final diacritics in Arabic words, not just pronouns.

- أَحمَد يَراه.

ʾaḥmad yarāh.

Ahmed sees him.

- الأُستاذُ يُناديك.

al-ʾustāḏu yunādīk.

The teacher is calling you (masculine).

- أُمّي تَشتاقُ إلَيّ عِندَما أَكون في المَدرَسَة.

ʾummī taštāqu ʾilayy ʿindamā ʾakūn fī al-madrasah.

My mother misses me when I’m at school.

Here’s a chart with the rest of the object construction.

| English | Arabic | Romanization |

|---|---|---|

| you (dual) | -كُما | -kumā |

| them (dual) | -هما | -humā |

| us | -نا | -nā |

| you (plural masculine) | -ك | -kum |

| you (plural feminine) | -ك | -kunn(a) |

| them (plural masculine) | -هم | -hum |

| them (plural feminine) | -هن | -hunn(a) |

That’s a little better! These Arabic pronoun suffixes, being a little less frequent, are more regular and therefore remind you more of the subject forms.

- جَمال يَكرَهُنا.

ǧamal yakrahunā.

Jamal hates us.

- حَميد يَعرِفُهُم.

ḥamīd yaʿrifuhum.

Hamid knows them (several men).

- هَل يَجِبُ أَن نَدعوهُم إلى الحَفلَة؟

hal yaǧibu ʾan nadʿūhum ʾilā al-ḥaflah?

Should we invite them (several women) to the party?

The object pronoun suffixes are extremely important. Why’s that? Well, because they get used over and over again!

Take a look.

4. Arabic Possessive Pronouns

The possessive pronouns in Arabic also take the form of suffixes. Much like how we might say “Malik’s hammer,” adding a suffix to the person who owns it, in Arabic we add the suffix to the thing being owned.

And congratulations, you basically know them all! Here’s the chart:

| English | Arabic | Romanization |

|---|---|---|

| my | -ي | -i |

| your (masculine) | -ك | -k(a) |

| your (feminine) | -ك | -k(i) |

| his | -ه | -h(u) |

| her | -ها | -hā |

| your (dual) | -كما | -kumā |

| their (dual) | -هما | -humā |

| our | -نا | -nā |

| your (plural masculine) | -كم | -kum |

| your (plural feminine) | -كن | -kun |

| their (plural masculine) | -هم | -hum |

| their (plural feminine) | -هن | -hun |

The chart above is virtually identical to the Object Pronouns chart. Just pay attention to the suffix for the first person singular, the equivalent of “my.” That was -ni as an object suffix for verbs, but when we slap it on a noun to show possession, it turns into -i.

As for the rest, throw those onto a noun and see what happens!

- هَذِهِ حَقيبَةُ سَفَري.

haḏihi ḥaqībaẗu safarī.

This is my suitcase.

- أَيْنَ سَيَّارَتُها؟

ʾayna sayyaāratuhā?

Where is her car?

- سائِقُهُم مُتَأَخِّر.

sāʾiquhum mutaʾaḫḫir.

Their (plural masculine) driver is late.

Memorized that chart yet? You’ve still got one more chance…

5. Arabic Prepositional Pronouns

Yes, that’s right. In Arabic, a pronoun can attach to a verb, a noun, or a preposition.

And some news you’re probably dying to hear is that the schema for pronouns on prepositions is exactly the same as the chart for possessive pronouns.

We’re not even going to print it again—we’ll jump straight to some examples.

- هَل يُمكِنُني المَشي مَعَك؟

hal yumkinunī al-mašī maʿak?

Can I walk with you (singular masculine)?

- هَذِهِ هَدِيَّة مِن عِندِهُن.

haḏihi hadiyyah min ʿindihun.

This is a present from them (two women).

- وَجَدتُ رِسالَة مَكتوبَة مِن طَرَفِها.

waǧadtu risal-ah maktūbah min ṭarafihā.

I found a letter written by her.

- المَطَر كانَ يَسقُطُ عَلَيّ.

al-maṭar kāna yasquṭu ʿalayy.

The rain was falling on me.

Note here that the word for “on,” which is ‘ala, has an irregular form, ‘alay, when it gets combined. So does li-, meaning “to.”

- تَدَحرَجَت الكُرَة إلَيْها و اِلتَقَطَتها.

tadaḥraǧat al-kurah ʾilayhā wa iltaqaṭathā.

The ball rolled to her and she picked it up.

Arabic, like all languages, has quite a wide array of prepositions.The irregularities are simply due to how often they’re used. That’s actually good news for you, since you’ll get the memories reinforced many times!

6. Arabic Demonstrative Pronouns

Tired of those charts? Don’t worry, just a few more. The demonstrative pronoun is for pointing out specific objects. It corresponds to the English words “this” and “that.” Naturally, the plural is equivalent to “these” and “those.”Arabic nouns have gender, and therefore the demonstrative pronouns do as well. Let’s look at a chart of the demonstrative pronouns in Arabic before diving a little bit deeper into the analysis.

| English | Arabic | Romanization |

|---|---|---|

| this (masculine) | هَذا | haḏā |

| these (masculine/feminine) | هؤلاء | hā’ulā’ |

| that (masculine) | ذلك | ḏālik(a) |

| those (masculine/feminine) | أولئك | ‘ulā’ik(a) |

| this (feminine) | هذه | hāḏih(i) |

| that (feminine) | تلك | tilka |

Your eyes don’t deceive you. The plural form of these demonstrative pronouns is, in fact, identical for both masculine and feminine nouns. Let’s see some examples.

- اِحضِر ذَلِكَ الكُرسي إلى هُنا.

iḥḍir ḏalika al-kursī ʾilā hunā.

Please bring that chair over here.

- اِحضِر تِلكَ الكَراسي إلى هُنا.

iḥḍir tilka al-karāsī ʾilā hunā.

Please bring those chairs over here.

- هَذِهِ الكَعكَة غالِيَة جِدّاً, لَكِن تِلكَ الكَعكَة رَخيصَة.

haḏihi al-kaʿkah ġal-iyah ǧiddan, lakin tilka al-kaʿkah raḫīṣah.

This cake is very expensive, but that cake is cheap.

We’ve omitted something here. The dual is back—but only for super, super formal Arabic. Most people speaking MSA in real life to you, or to speakers from other regions, won’t use it.

One more complication, though, is that in the dual form, demonstrative pronouns in Arabic decline for case as well. There’s a tiny distinction made between simply saying “those two” (the nominative case) and “to those two / of those two” (the accusative and genitive cases, respectively).

Does this sound like a very uncommon thing to say? It definitely is—and that’s why it’s only used in the most formal of situations.

7. Pronouns in Arabic Dialects

So as you may know, Modern Standard Arabic is a slightly artificial language. That means it has rules that people try to follow as they speak, instead of natural rules that come from everybody speaking the same way in one area.

Dialects, on the other hand, have those natural rules, and people speak without feeling any pressure to follow rules that were laid down by any language authorities.

How does this relate to pronouns? For you, the learner, it’s good news. You have to remember less!

First, the dual is gone. Colloquial Arabic varieties don’t retain the dual form anymore, instead replacing it with the plural.

Second, the plural forms usually don’t distinguish between masculine and feminine. The masculine plural is sufficient for speaking about men, women, or a group of both men and women.

As a foreign learner, balancing your speech between perfect grammatical correctness and colloquial idiomatic language is an endless task, so you should be aware of these possible changes and adjust your speech to the environment you find yourself in.

8. Conclusion

Understanding Arabic pronouns is no easy feat, but hopefully these Arabic pronoun rules and examples will shed some light on why Arabic grammar is considered to be beautifully intricate.

Can you appreciate that beauty? Or would you rather pick up the language by example instead of by rule?

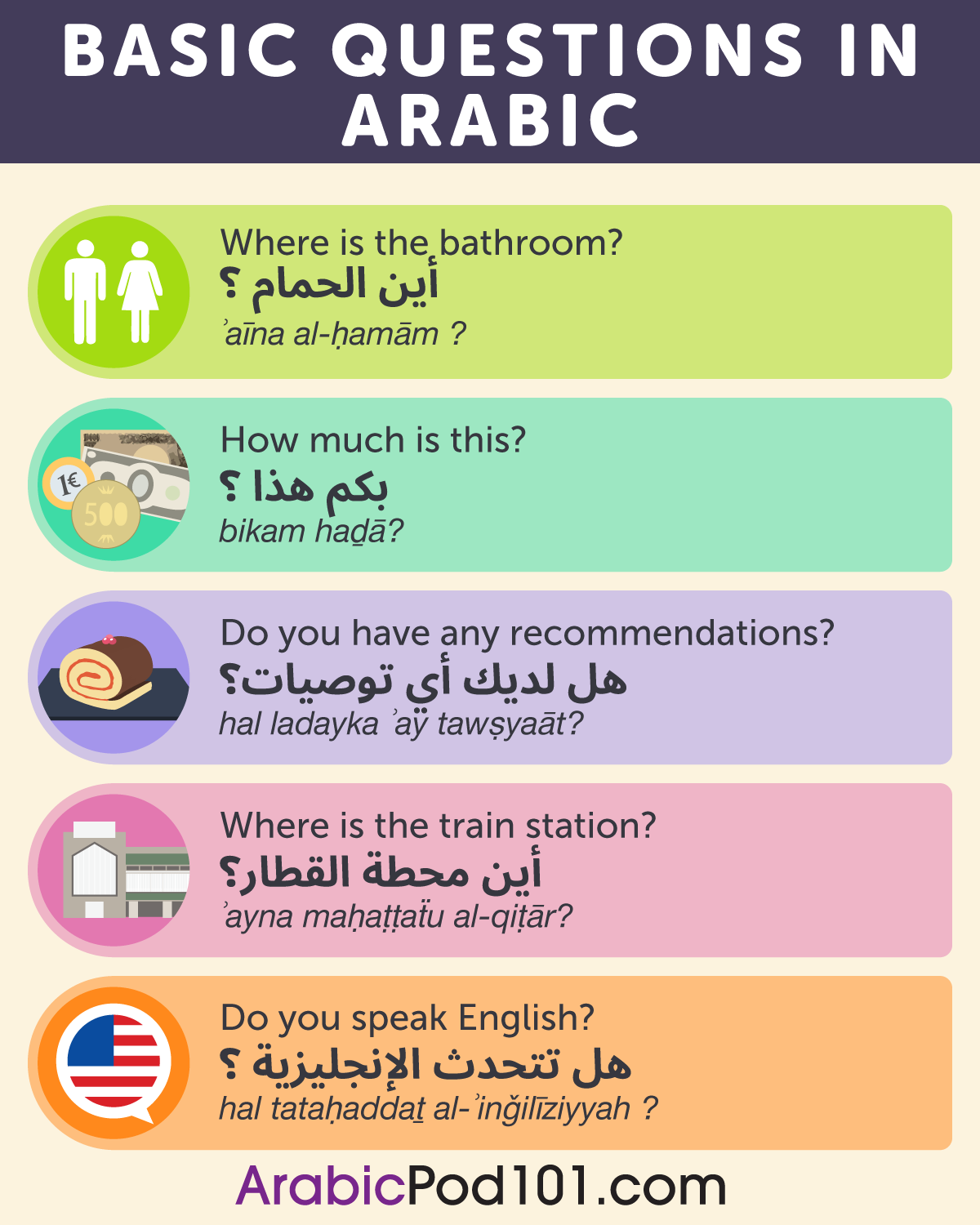

At ArabicPod101.com, you can do both. Just from learning by yourself, you can lay a strong foundation of grammar rules and then back it up with the experience of listening to real spoken Arabic by native speakers.

Those are two pieces of the same puzzle—and using both in conjunction is what’s going to get you to the highest possible level in the Arabic language.

If you found this Arabic pronouns lesson helpful, you may want to read the following articles on ArabicPod101 as well:

- 100 Arabic Nouns You Can’t Live Without

- 100+ All-Purpose Arabic Adjectives

- Your Ultimate Language Guide to Arabic Conjunctions

Happy Arabic learning!